In Death, Rachel Scott Becomes A Powerful Witness For Christ

Rachel Scott was having lunch with a friend outside when the horror began to unfold at Columbine High School near Denver on April 20, 1999.

Two of their classmates, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, approached with guns and fired several shots, wounding both.

As the boy lay stunned and Rachel tried to crawl away, Harris lifted Rachel by her hair and asked, “Do you believe in God?”

“You know I do,” she answered.

“Then go be with him,” Harris said, and shot her in the head.

She was the first to die that morning.

Rachel was 17, and in the year before her murder she had grown more committed in her relationship with God.

Like most teenagers, she struggled with things like sexual temptation and alcohol abuse. She was no perfect saint, but something had changed. She had become kinder to others, including those like Dylan and Eric, who were part of the “trench coat mafia” — teens who dressed in black, listened to nihilistic music, played violent video games and hated Christ and Christians.

In an Internet video, Klebold said, “Thank God they crucified that a______.”

Rachel counted the cost of her decision to follow Christ and suffered the deep pain of loneliness when her friends at Columbine turned away from her because of her faith. But she would not go back.

In one of her journal entries, dated April 20, 1998 — exactly one year to the day before she died — she wrote: “I am not going to apologize for speaking the Name of Jesus, I am not going to justify my faith to them, and I am not going to hide the light that God has put into me. If I have to sacrifice everything … I will.”

A few days later, she wrote: “This will be my last year, Lord. I have gotten what I can. Thank you.”

She often told friends she believed she would die young and wouldn’t live long enough to marry or have children.

Sometime after she died, her father, Darrell Scott, received a telephone call from a stranger in Ohio. The man told Darrell “you’ll probably think I’m crazy when I tell you why I called, but I have had a recurring dream about your daughter. …”

In his dream, the man said, he had seen a stream of tears flowing from Rachel’s eyes, and they were watering something, but he couldn’t see what it was.

Would that mean anything to him or his family, the man asked.

No, Darrell said, it didn’t mean a thing. But he took down the man’s number and promised to call if it ever did mean anything.

Darrell had forgotten about the strange message until seven days later when he got a call from the sheriff’s office telling him he could pick up the contents of his daughter’s school backpack, which had been riddled by bullets.

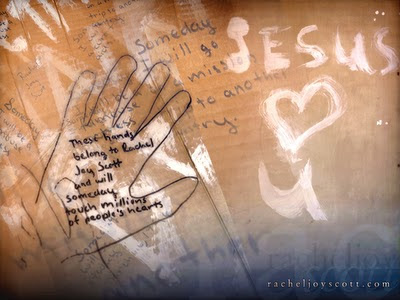

Sitting in his truck, Darrell sorted through Rachel’s belongings and read through her final diary. When he got to the last page, there was a picture Rachel had drawn the morning she was murdered. It was of a pair of eyes crying, and the 13 tears turned to drops of blood as they watered a rose that grew out of a Columbine plant.

Thirteen was the number of victims that Harris and Klebold killed that day before taking their own lives.

I heard Darrell Scott tell this story to a crowd of thousands of teenagers at Ichthus in Wilmore, Ky., in April 2002 — days after a similar deadly rampage at a secondary school in Germany.

He believed his daughter knew she would be used by God for something good. She had said she would touch millions of lives around the world. On the day of her funeral, which was a tribute to her faith, CNN had its largest audience ever.

Rachel believed little acts of kindness could make a big difference as others paid them forward.

“I have a theory that if one person will go out of their way to show compassion, it will start a chain reaction of the same,” she wrote.

Ironically, at almost the same time, Eric Harris had also used the phrase “chain reaction” in one of his hate-filled messages: “We need to start a revolution,” he said. “We need to get a chain reaction going here.”

Some would say these things are coincidences and that it’s naive to think tragedies like Columbine have any meaning. There was a time I would have thought so too. I’m a journalist with a liberal arts education and therefore prone to skepticism. At times, I have doubted that God exists. But I’ve come to believe there is a struggle going on in our world between the spiritual forces of darkness and light.

What other explanation could there be for the Holocaust or the horror of Rwanda in 1994, when nearly a million people were butchered by their neighbors? How else could one account for the incredible stories of forgiveness, redemption and grace that followed those tragedies? And how else could the death of a 17-year-old girl in Colorado lead hundreds of young people at a rock music festival in Wilmore to come forward to repent of their sins and choose to be reborn into a more abundant life?

I believe that at the end of this spiritual conflict, Christ will be the victor and will make all things new, as he promised. It is a struggle in which no one can remain neutral. Rachel Scott learned that at a tender age and chose a side.

Which side are you on?

by Randy Patrick

No comments:

Post a Comment